Werner Herzog in Ireland

A few words on Werner Herzog, taking in: Skellig Michael and Skellig Bheag; Ballinskelligs, Co. Kerry; Reek Sunday; Croagh Patrick; Popol Vuh; Joy Division; Ian Curtis; Factory Records; dead wax inscriptions; Fitzcarraldo; Aguirre, the Wrath of God; Heart of Glass; The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser; cinema lobby cards and secondhand records.

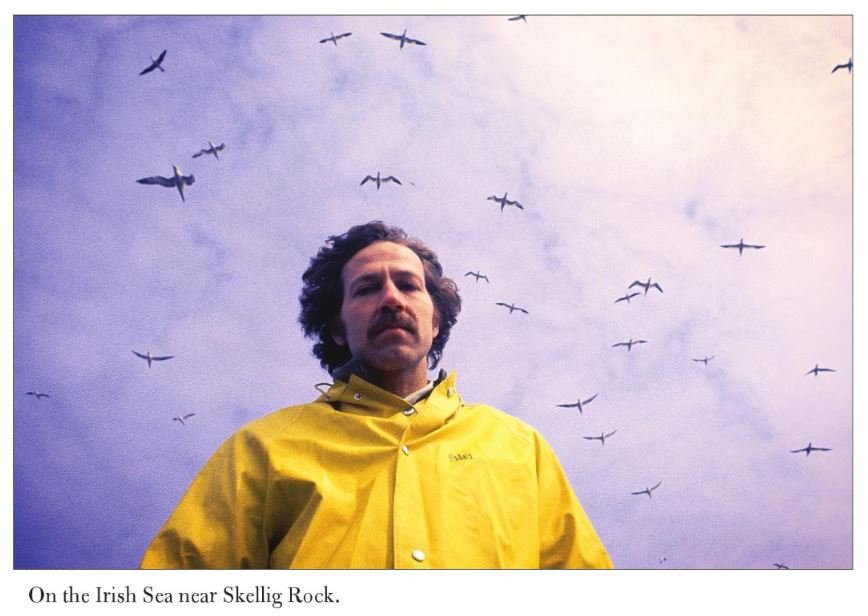

Werner Herzog on Skellig Michael. Skellig Bheag behind him. Photograph by Alan Greenberg, taken from his book: Every Night the Trees Disappear: Werner Herzog and the Making of Heart of Glass (Chicago Review Press, 2012).

“I once stayed at a tiny guesthouse in Ballinskelligs. The landlady asked me what I did, and off the top of my head - I don’t know why - I said, ‘I am a poet’. She opened the doors wide and gave me the room for half price. At home they would have thrown me out into the street.” Werner Herzog (Herzog on Herzog, 2002)

I watched my first Werner Herzog film in 1990. I was enrolled on a Bachelor of Commerce in UCC but I spent more time in the Boole Library watching films than I did attending lectures. I watched Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972) over and over. It remains one of my favourite films. Herzog’s films led me to the music of Florian Fricke and his band Popol Vuh. Fricke was a friend and longtime collaborator of Herzog’s composing music for five of the director’s films.

In 2007 I found a copy of Popul Vuh’s Aguirre in Barcelona at an outdoor record stall in front of Basílica de Santa Maria del Pi. As I flicked through boxes people formed giant circles around the tables of records and danced the “Sardana”, a traditional Catalan dance. That was a great day, a mint copy of Aguirre for only €10. The dancing was pretty impressive too.

Popol Vuh - Aguirre (1982, PDU). Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Ten years after Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Herzog returned to Peru and filmed Fitzcarraldo (1982). My first online purchase was an original set of four German cinema lobby cards - used to promote the film - that I won in an Ebay auction. I got lucky, I was the only bidder and scored them cheap as chips. But who else was going to bid on a set of old Herzog lobby cards?

One of the lobby cards is a photograph of Fitzcarraldo’s ship being pulled over the mountain. It’s stunning.

Fitzcarraldo 1982 Lobby Card. Photograph by Paul McDermott.

In the ten years between these two iconic films Herzog directed five others. Stroszek (1977) was reported to have been the film that Ian Curtis watched a few hours before he took his own life. Stroszek ends with a shot of a dancing chicken.

Factory Records made reference to this scene on Joy Division’s posthumous double album Still. The dead wax on Side A contains the inscription “The chicken won’t stop”. Sides B and C have chicken tracks and Side D is inscribed with the legend “the chicken stops here”. In my late teens when I played Still I would tilt the vinyl into the light to read these messages and wonder what they meant. Tony Wilson was always the master at myth-making.

Joy Division - Still (Factory Records: FACT 40, 1981). Side A: “The chicken won’t stop”. Side B: 3 pairs of chicken tracks. Side C: 2 pairs of chicken tracks. Side D: “The chicken stops here”. Photographs by Paul McDermott.

Between Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo Herzog made two other films with Klaus Kinski: Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), his remake of F. W. Murnau’s 1922 German Dracula adaptation Nosferatu, and Woyzeck (1979). Herzog would work with Kinski once more on Cobra Verde (1987). Despite universal acclaim for his Noughties documentaries - Grizzly Man (2005), Encounters at the End of the World (2007) and Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010), the five films with Kinski are probably the most famous films that Herzog has directed in a long and illustrious career. He revisits his tumultuous working relationship with Kinski in his fantastic 1999 documentary My Best Fiend.

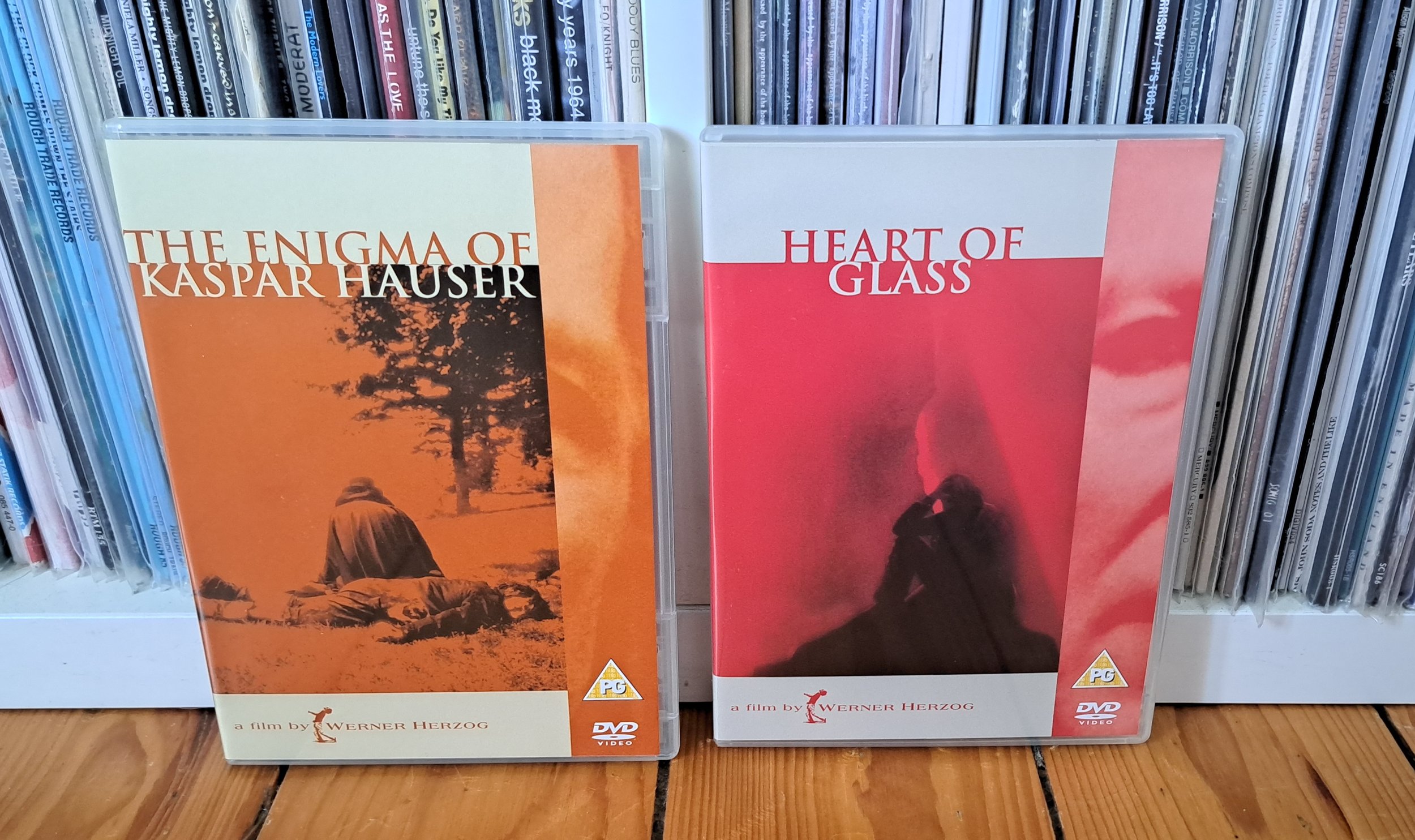

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) and Heart of Glass (1976). Photograph by Paul McDermott.

It’s the two films that Herzog made directly after Aguirre, the Wrath of God that both have an Irish connection: The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974) and Heart of Glass (1976).

Still from The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974).

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser is based on the true story of a young man who has lived the first seventeen years of his life chained in a tiny cellar, barely able to speak and walk, he mysteriously appears in the town square one morning during the year 1828 in Nuremberg, Germany. Hauser learns to read and write. He is physically attacked leaving him unconscious with a bleeding head. He recovers, but is again mysteriously attacked. As he recovers in bed he describes visions he has had. The scene cuts to a rock-strewn hillside shrouded in mist. The familiar sound of ‘Canon in D for Strings and Continuo’ rises as the camera focuses on small figures making their way up the hillside. The scene is less than a minute in duration and was filmed during a Reek Sunday pilgrimage on Croagh Patrick.

“For Kaspar’s vision of the people scaling the mountainous rock face, we went to the west coast of Ireland. Every year there is a great procession on this foggy mountain, the Croagh Patrick, with over 50,000 people.”

Werner Herzog (Herzog on Herzog, 2002)

On the audio commentary that accompanied the 2005 DVD release of The Enigma Kaspar Hauer, Herzog says: “It was shot in Ireland on Croagh Patrick where 80,000 or so pilgrims climb this mountain where St. Patrick fasted for 40 days and wrestled with an angel. I was always fascinated about that.”

The number of pilgrims may have changed in his retelling of the story, but there is no doubting the sincerity of Herzog’s feeling towards the Reek. Norman Hill, moderating the audio commentary, states that the Croagh Patrick scene is very strange. Herzog responds:

“It has no context to the pure narration of the film but it is a very essential strange part of the thing. Sometimes it happens in storytelling that things on first sight do not fit into it. Everyone in Hollywood and every screenwriting guru would tell you to take that out it doesn’t belong there. They do not understand that sometimes there is a mysterious way, a motif or an image or a form of speech belongs more deeply there than anything else and that is the power of film sometimes. It’s inexplicable and very mysterious and does not follow the laws of storytelling at all anymore.”

Werner Herzog - Audio Commentary (The Enigma Kaspar Hauer. Anchor Bay, 2005)

Skellig Michael and Skellig Bheag on the sleeve of Popol Vuh’s Coeur de Verre (Heart of Glass) (1977, Egg Records). Photograph by Paul McDermott.

Two years later Herzog was back in Ireland to film the final scenes to his next film Heart of Glass.

Heart of Glass is set in 18th-century Bavaria. A town’s glassblowing factory produces ruby glass but when the master glass blower dies, the secret of producing it is lost. The factory owner is obsessed with the ruby glass believing it to have magical properties. With the loss of the secret, he descends into madness. The villagers also become bewitched by the secrets of glass. My copy of Popol Vuh’s soundtrack is a French edition that I found in a record shop in Brussels. Infamously during the production of the film Herzog hypnotised the actors.

“The reasons for the experiments with hypnosis are quite simple. The script was loosely adapted from a chapter of Herbert Achternbusch’s novel The Hour of Death which was, in turn, based on an old Bavarian folk legend about a peasant prophet in Lower Bavaria who, like Nostradamus, made predictions about the cataclysmic end of the world. In the film Hias - a shepherd with prophetic gifts - has apocalyptic visions and foresees an entire town becoming halfway insane and the destruction by fire of its glassworks. At the end of the film the factory-owner burns his own factory down, as foreseen, and the prophet is then blamed for the fire.

At the time I knew very little about hypnosis and it never crossed my mind to use it in a film until I started to think about the story I had before me, one about collective madness, one that calls for these characters to be aware of the catastrophe that is approaching, yet one they continue to walk straight into. I wondered how I could stylize everyone who, almost like sleepwalkers with open eyes, as if in a trance, were walking into this foreseeable disaster. I wanted actors with fluid, almost floating movements, which meant the film would seem to depart from known behaviour and gestures and would have an atmosphere of hallucination, prophecy and collective delirium that intensifies towards the end.”

Werner Herzog (Herzog on Herzog, 2002)

Werner Herzog on Skellig Michael “hurling granite shards into the void”. Photographs by Alan Greenberg, taken from his book: Every Night the Trees Disappear: Werner Herzog and the Making of Heart of Glass (Chicago Review Press, 2012).

According to the writer and director Alan Greenberg, who accompanied Herzog to Co. Kerry, the plan to film the ending of Heart of Glass on Skellig Michael was an afterthought. “When he finished the scenario, with the population gone mad and Hias alone on his mountaintop, Herzog envisioned something else, an image that emerged from a forbidding, mountainous crag ten miles or so off the sullen, southwest coast of Ireland, a towering islet known as Skellig Rock” (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012).

“The final sequence was filmed on Skellig Rock, a truly ecstatic landscape out there in Ireland. It is a rock almost like a pyramid that rises almost 300 metres out of the ocean where in the year 1000 AD the marauding Norsemen threw the inhabiting monks off into the sea. It took hours and hours of sailing in small boats through the rain and the cold just to get there, and only during the summer is it possible to land there as it is otherwise too windswept.”

Werner Herzog (Herzog on Herzog, 2002)

Stills from Heart of Glass (1976).

The prophet Hias would have a vision of a solitary figure standing on the brink of a precipice atop Skellig Michael.

“The breakers rise thirty or forty metres vertically up the sides of it. Up at the top there is mist, steam and a sloping plateau. You have to climb hundreds of steps, carved out of the stone by the monks. Hias has a vision of a man standing up there, one of those who have yet to learn that the Earth is round. He still believes that the Earth is a flat disc that ends in an abyss somewhere far out in the ocean. For years he stands staring out over the sea until several more men join him. One day they resolve to take the ultimate risk: they take a boat and start to row out to sea. In the last shot of the film you can see the ocean growing dark, deep heavy clouds and long drawn-out waves, and the four men rowing their boat out into the totally grey open sea.”

Werner Herzog (Herzog on Herzog, 2002)

Still from Heart of Glass (1976).

The film would end on a note of “Hope”. Herzog explained his plan for the final sequence to Walter Saxer, the film’s production manager. According to Greenberg, “Saxer snarled that “hope” was something he could do without. He maintained that shooting this extra scene would add many thousands of dollars to the slender budget and create a mass of logistical headaches,” (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012).

Herzog prevailed and set about contacting a fisherman named Fitzgerald in Ballinskelligs asking if the seas were navigatable for a crossing to Skellig? “No, but maybe in a week or so,” replied the fisherman, “you never know, sometimes a boat can’t find its way through the twenty-foot swells surrounding Great Skellig for weeks or even months, while other times the water’s just like glass,” (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012).

Undeterred Herzog, accompanied by his cast and small crew, made their way to Ballinskelligs. Greenberg describes seeing the Skelligs for the first time:

“More than ten miles into the Atlantic, just under the horizon, the gray peak hovered in a shallow haze, far away. Surrounding Skellig Rock were two smaller crags, Little Skellig and Washerwoman’s Rock, with a third the Isle of Many Fears, nowhere to be seen.”

Alan Greenberg (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012)

The team hired a boat and set sail. Ninety minutes later they approached Skellig Bheag, “a stern hulk that seemed oddly two-dimensional and was blanketed white with twenty-thousand gannets,” (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012). They sailed on and landed on Skellig Michael. The team rushed up the stone steps. At the monastery, “Herzog bent his knee and walked through an isolated sovereign doorway, then came upon the igloo-shaped clochans,” (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012).

Stills from Heart of Glass (1976).

“Herzog headed up the long, hard slope of the precipice. Standing at the edge, which the monks had called the Stone of Pain, Herzog began hurling granite shards into the void. Out of the shadows way below, wave upon wave of birds flew out to sea.”

Alan Greenberg (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012)

The following day the team had planned to sail out to the Skelligs and film but bad weather made reaching the rocks impossible. Herzog instead hired a helicopter to get the actors and crew out to Skellig Michael. The helicopter pilot told Herzog that, “the landings would present quite a risk, but he’d give it a go,” (Every Night the Trees Disappear, 2012). Once out on the Rock the weather improved and the filming went ahead. Cast and crew worked late into the evening and Herzog got the shots he wanted. The helicopter ferried the team in groups of four back to Ballinskellings but because the team had worked too long darkness was falling. The helicopter couldn’t fly at night so some of the actors and team members were left stranded and slept on Skellig Michael.

On the audio commentary that accompanied the 2005 DVD release of Heart of Glass, Herzog says: “I love this place, it’s actually Skellig Rock. It’s a spectacular place, I truly love it, it is an ecstatic landscape for me.” When asked if it was difficult filming on the rock he laughs and says:

“Don’t ask me how difficult it was, it was hours and hours in small boats, everybody was getting sick and vomiting, freezing and rain and whatever. The musicians played music that I really love a lot, medieval music on old instruments, and it’s all live performed out on this rock.”

Herzog - Audio Commentary (Heart of Glass. Anchor Bay, 2005)

Still from Heart of Glass (1976).

The experience of filming on Skellig Michael left a lasting impression on Herzog. He named his imprint that published his screenplays “Skellig” and he named the production company that produced his 2011 documentary Into the Abyss, “Skellig Rock”.

In 2008 Herzog was asked by movies.ie if he had ever been to Ireland? Herzog confirmed that he had been to Ireland several times and continued:

“I can tell you something, if I have to go into exile, because of fascism rising again in Germany, or rising here in the United States, I would show up in Connemara.”

Heart of Glass (Skellig Edition, 1976) by Alan Greenberg (including the screenplay by Herzog). Republished in 2012 as Every Night the Trees Disappear: Werner Herzog and the Making of Heart of Glass.

References:

Greenberg, Alan and Herzog, Werner. Every Night the Trees Disappear: Werner Herzog and the Making of Heart of Glass. Chicago Review Press, 2012.

Herzog, Werner, and Cronin, Paul. Herzog on Herzog. Faber and Faber, 2002.

Werner Herzog photographed by Alan Greenberg, taken from his book: Every Night the Trees Disappear: Werner Herzog and the Making of Heart of Glass (Chicago Review Press, 2012).

Postscript*

In 2017 Werner Herzog was back in Ireland appearing at the International Literature Festival Dublin in the NCH on 21 May. After the event Herzog and his wife Lena headed South. A few days later Lena posted the below photograph on her Instagram writing, “we made it on Skellig Michael, and were lucky (choppy waters). So we circled the other islands; it was really beautiful.”

Photograph by Lena Herzog.

*Thanks to John Foley for the tip #grma